DON ISAAC ABARBANEL

His Life and Times

Don Isaac Ben Judah Abarbanel (born in Lisbon 1437, died in Venice 1508) worthily closes the list of Jewish statesmen in Spain who, beginning with Chasda Ibn-Shaprut, used their names and positions to protect the interests of our people. In his noble mindedness, his contemporaries saw proofs of Abarbanel’s descent from the royal of house of David, a distinction of which the Abarbanels prided themselves, and which was generally conceded to them. His grandfather, Samuel Abarbanel, who, during the persecution of 1391, but probably only for a short time, lived as a Christian, was a large hearted, generous man, who supported Jewish learning and its votaries. His father, Judah, treasurer to a Portuguese prince, was wealthy and benevolent. Isaac Abarbanel was precocious, of clear understanding, but sober-minded.

Don Isaac Ben Judah Abarbanel (born in Lisbon 1437, died in Venice 1508) worthily closes the list of Jewish statesmen in Spain who, beginning with Chasda Ibn-Shaprut, used their names and positions to protect the interests of our people. In his noble mindedness, his contemporaries saw proofs of Abarbanel’s descent from the royal of house of David, a distinction of which the Abarbanels prided themselves, and which was generally conceded to them. His grandfather, Samuel Abarbanel, who, during the persecution of 1391, but probably only for a short time, lived as a Christian, was a large hearted, generous man, who supported Jewish learning and its votaries. His father, Judah, treasurer to a Portuguese prince, was wealthy and benevolent. Isaac Abarbanel was precocious, of clear understanding, but sober-minded.

The origin of Judaism, its splendid antiquity, and its conception of God were favorite themes with Abarbanel from his youth upward, and when still quite a young man he published a treatise setting forth the providence of God and its special relation to Israel. On the other hand he was a solid man of business, who thoroughly understood finance and affairs of state. The reigning king of Portugal, Don Alfonso V, an intelligent, genial, amiable ruler, was able to appreciate Abarbanel’s talents; he summoned him to his court, confided him the conduct of financial affairs, and consulted him on all important state questions. His noble disposition, his sincerely devout spirit, his modesty, far removed from arrogance, and his unselfish prudence, secured for him at court, and far outside its circle, the esteem and affection of Christian grandees. Abarbanel stood in friendly intimacy with the powerful, but mild and beneficent Duke Ferdinand of Braganza, lord of fifty towns, boroughs, castles and fortresses, and able to bring 10,000 foot-soldiers and 3,000 cavalry into the field, as also with his brothers, the Marquis of Montemar, Constable of Portugal, and the Count of Faro, who lived together in fraternal affection. With the learned John Sezira, who was held in high consideration at court, and was a warm patron of the Jews, he enjoyed close friendship. Abarbanel thus describes his happy life at the court of King Alfonso:

“Tranquility I lived in my inherited house in fair Lisbon. God had given me blessings, riches and honor. I had built myself stately buildings and chambers. My house was the meeting-place of the learned and the wise. I was a favorite in the palace of Alfonso, a mighty and upright king, under whom the Jews enjoyed freedom and prosperity. I was close to him, was his support, and while he lived I frequented his palace”.

Alfonso’s reign was the end of the golden time for the Jews of the Portugal. Although in his time the Portuguese code of laws (Ordenaoens de Alfonso V), containing Byzantine elements and canonical restrictions for the Jews, was completed, it must be remembered that on the one hand, the king, who was a minor at the time, had had no share in framing them, and on the other, the hateful laws were not carried out. In his time the Jews in Portugal bore no badge, but rode on richly caparisoned horses and mules, wore costume of the country, long coats, fine hoods and silken vests, and carried gilded swords, so that they could not be distinguished from Christians. The greater number of tax-farmers (Rendeiros) in Portugal were Jews. Princes of the church even appointed Jewish receivers of church taxes, at which the cortes of Lisbon raised complaint. The independence of the Jewish population under the chief rabbi and the seven provincial rabbis was protected in Alfonso’s reign, and included in the code. This code conceded to Jews the right to print their public documents in Hebrew, instead of in Portuguese as hitherto commanded.

Abarbanel was not the only Jewish favorite at Alfonso’s court. Two brothers Ibn-Yachya Negro also frequented the court of Lisbon. They were sons of a certain Don David, who had recommended them not to invest their rich inheritance in real estate, for he saw that banishment was in store for the Portuguese Jews.

Abarbanel was not the only Jewish favorite at Alfonso’s court. Two brothers Ibn-Yachya Negro also frequented the court of Lisbon. They were sons of a certain Don David, who had recommended them not to invest their rich inheritance in real estate, for he saw that banishment was in store for the Portuguese Jews.

As long as Isaac Abarbanel enjoyed the King’s favor, he was a “shield and a wall for his people, and delivered the sufferers from their oppressors, healed differences, and kept fierce lions at bay,” as described by his poetical son, Judah Leon. He who had a warm heart for all afflicted, and was father to the orphan and consoler to the sorrowing, felt yet deeper compassion for the unfortunate of his own people. When Alfonso conquered the port of Arzilla in Africa, the victors brought with them, among many thousand captive Moors, 250 Jews, who were sold as slaves throughout the kingdom. That Jews should be doomed to the miseries of slavery was unendurable to Abarbanel’s heart. At his summons a committee of twelve representatives of the Lisbon community was formed, and collected funds; then with a colleague, he traveled over the whole country and redeemed the Jewish slaves, often at a high price. The ransomed Jews, adults and children, were clothed, lodged, and maintained until they had learned the language of the country, and were able to support themselves.

When King Alfonso sent an embassy to Pope Sixtus IV to congratulate him upon his accession to the throne, and to send him tidings of his victory over the Moors in Africa, Doctor John Sezira was one of the ambassadors. One in heart and soul with Abarbanel, and friendly to the Jews, he promised to speak to the pope in their favor and behalf. Abarbanel begged his Italian friend, Yechiel of Pisa, to receive John Sezira with a friendly welcome, to place himself entirely at his disposal, and convey to him, and to the chief ambassador, Lopes de Almeida, how gratified the Italian Jews were to hear of King Alfonso’s favor to the Jews in his country, so that the king and his courtiers might feel flattered. Thus Abarbanel did everything in his power for the good of his brethren.

In the midst of prosperity, enjoyed with his gracious and cultured wife and three fine sons, Judah Leon, Isaac and Samuel, he was disturbed by the turn of affairs in Portugal. His patron, Alfonso V, died and was succeeded by Don Joao II (1481-1495), a man in every way unlike his father -- stronger of will, less kindly, and full of dissimulation. He had been crowned in his father’s lifetime, and was not rejoiced when Alfonso, believed to be dead, suddenly re-appeared in Portugal. Joao II followed the tactics of his unscrupulous contemporary, Louis XI of France, in the endeavor to rid himself of the Portuguese grandees in order to create an absolute monarchy. His first victim was to be Duke Ferdinand of Braganza, of royal blood, almost as powerful and as highly considered as himself, and better beloved. Don Joao II was anxious to clear from his path his duke and brothers, against whom he had a personal grudge. While flattering the Duke of Braganza, he had a letter set up against him, accusing him of a secret, traitorous understanding with the Spanish sovereigns, the truth of which has not to this day been satisfactorily ascertained. He arrested him with a Judas kiss, caused him to be tried as a traitor to his country, sent him to the block, and took possession of his estates and wealth (June 1483). His brothers were forced to flee to avoid a like fate. Inasmuch as Isaac Abarbanel had lived in friendly relations with the Duke of Braganza and his brothers, King Joao chose to suspect him of having been implicated in the recent conspiracies. Enemies of the Jewish statesman did their best to strengthen these suspicions. The king sent a command for him to appear before him. Not suspecting any evil, Abarbanel was about to obey, when an unknown friend appeared, told him his life was in danger, and counseled to hasty flight. Warned by the fate of the Duke of Braganza, Abarbanel followed the advice, and fled to Spain. The king sent mounted soldiery after him, but they could not overtake him, and he reached the Spanish border in safety. In a humble but manly letter he declared his innocence of crime, and also the innocence of the Duke of Braganza. The suspicious tyrant gave no credence to the letter of defense, but caused Abarbanel’s property to be confiscated, as also that of his son, Judah Leon, who was already following the profession of physician. His wife and children, however, he permitted to remove

to Castile.

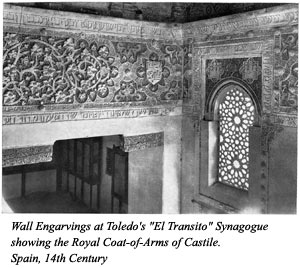

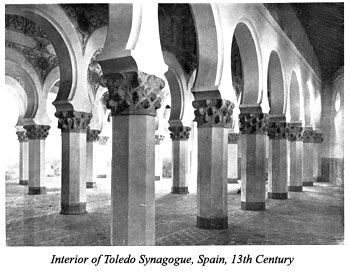

In the city of Toledo, where he found refuge, Isaac Abarbanel was honorably received by the Jews, especially by the cultured. A circle of learned men and disciples gathered round the famous, innocently persecuted Jewish statesman. With the rabbi, Isaac Aboab, and with the chief tithe-collector, Abraham Senior, he formed a close friendship. The latter, it seems, at once took him into partnership in the collection of taxes. Abarbanel’s conscience pricked for having neglected the study of the Law in following state affairs and mammon, and he attributed his misfortunes to the just punishment of heaven. He at once began to write, at the earnest entreaty of his friends, an exposition of books of the earlier prophets, on account of their apparent simplicity, neglected by commentators. As he had given thought to them before, he soon completed the work. Certainly, no one was better qualified than Abarbanel to expound historical biblical literature. In addition to knowledge of languages, he had experience of the world, and insight into political problems and complications necessary for unraveling the Jewish records.

In the city of Toledo, where he found refuge, Isaac Abarbanel was honorably received by the Jews, especially by the cultured. A circle of learned men and disciples gathered round the famous, innocently persecuted Jewish statesman. With the rabbi, Isaac Aboab, and with the chief tithe-collector, Abraham Senior, he formed a close friendship. The latter, it seems, at once took him into partnership in the collection of taxes. Abarbanel’s conscience pricked for having neglected the study of the Law in following state affairs and mammon, and he attributed his misfortunes to the just punishment of heaven. He at once began to write, at the earnest entreaty of his friends, an exposition of books of the earlier prophets, on account of their apparent simplicity, neglected by commentators. As he had given thought to them before, he soon completed the work. Certainly, no one was better qualified than Abarbanel to expound historical biblical literature. In addition to knowledge of languages, he had experience of the world, and insight into political problems and complications necessary for unraveling the Jewish records.

He had advantage over other expositors in using the Christian exegetical writings of Jerome, Nicholas de Lyra, and the baptized Paul of Burgos, and taking from them what was most valuable. Abarbanel, therefore, in these commentaries, shed light upon many obscure passages. They are conceived in a scholarly style, arranged systematically, and before each book appears a comprehensible preface and a table of contents, an arrangement copied from Christian commentators, and adroitly turned into account by him. Had Abarbanel not been so diffuse in style, and not had the habit of introducing each Scriptural chapter with questions, his dissertations would have been, or, at all events, would have deserved to be, more popular. Abarbanel accepted the orthodox point of view of Nachmani and Chasda, merely supplementing them with commonplaces of his own. He was not tolerant enough to listen to a liberal Judaism and its doctrines, and accused the works of Albalag and Narboni of heresy, classing these inquirers with the unprincipled apostate, Abner-Alfonso, of Valladolid. He was no better pleased with Levi Ben Gerson, because he had resorted to philosophical interpretations in many cases, and did not accept miracles unconditionally. Like the strictly Orthodox Jews of his day, such as Joseph Jaabez, he was persuaded that the humiliations and persecutions suffered by the Jews of Spain were due to their heresy.

Only a brief time was granted to Abarbanel to pursue his favorite study; the author was once more compelled to become a statesman. When about to delineate Judn and Israelite monarchs, he was summoned to the court of Ferdinand and Isabella to be entrusted with the care of finances. The revenues seem to have prospered under his management, and during his eight years of office (March, 1484-March, 1492) nothing went wrong with them. He was very useful to the royal pair by reason of his wisdom and prudent counsel. Abarbanel himself relates that he grew rich in the king’s service, and bought himself land and estates, and that from the court and the highest grandees he received great consideration and honor. He must have been indispensable, seeing that the Catholic sovereigns, under the very eyes of the malignant Torquemada, and in spite of canonical decrees and all the resolutions repeatedly laid down by the cortes forbidding Jews to hold office in the government, were compelled to entrust this Jewish minister of finance with the mainspring of political life!

How many services Abarbanel did for his own people during his time of office, grateful memory could not preserve by reason of the storm of misfortunes which broke upon the Jews later, but in Castile, as he had been in Portugal, he was as a wall of protection to them. Lying and fearful accusations from the bitter foes, the Dominicans, were not wanting. At one time it was said that the Jews had shown disrespect to some cross; at another, that in the town of La Guardia they had stolen and crucified a Christian child. From this tissue of lies, Torquemada fabricated a case against the Jews, and commended the supposed criminals to the stake. In Valencia, they were declared to have made a similar attempt, but to have been interrupted in the deed (1448-1490). That the Castilian Jews did not suffer extinction for the succor they afforded the unfortunate Marranos, was certainly owing to Abarbanel.

Meantime began the war with Granada, so disastrous for the Moors and Jews, which lasted ten years (1481-1491). To this the Jews had to contribute. A heavy tax was laid upon the community (Alfarda-Stangers Tax), on which the royal treasurer, Villaris, insisted with the utmost strictness. The Jews were, so to say, made to bring the logs to their own funeral pyre, and the people, adding insult to injury, mocked them. In the province of Granada, which by pride had brought about its own fall, there were many Jews, their numbers having been increased by the Marranos who had fled there to avoid death at the stake. Their position was not enviable, for Spanish hatred of Jews was strongly implanted there.

After long and bloody strife the beautiful city of Granada fell into the hands of the proud Spaniards. Frivolous Muley Abu-Abdallah (Boabdil), the last king, signed a secret treaty with Ferdinand and Isabella (25th November, 1491) to give up the town and its territory by a certain time. The conditions, seeing that independence was lost, were tolerably favorable. The Moors were to keep their religious freedom, their civil laws, their right to leave the country, above all their manners and customs, and were only required to pay the taxes which hitherto they had paid the Moorish king. The renegades -- that is to say, Christians who had adopted Islam, or, more properly speaking, the Moorish pseudo-Christians -- who had fled from the Inquisition to Granada, and returned to Islam, were to remain unmolested. The Inquisition was not to claim jurisdiction over them. The Jews of the capital of Granada, of Albaicin quarter, the suburbs and the Alpujarras, were included in the provisions of the treaty. The were to enjoy the same indulgences and the same rights, except that relapsed Marranos were to leave the city, only the first month after its surrender being the term allowed for emigration; those who stayed longer were to be handed over to the Inquisition. One noteworthy point stipulated by the last Moorish king of Granada, was that no Jew should be set over the vanquished Moors as officer of justice, tax gatherer, or commissioner. On January 2nd, 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella, with their court, amid ringing of bells, and great pomp and circumstance, made their entry into Granada. The Mahometan kingdom of the Peninsula had vanished like a dream in an Arabian Night’s legend. The last prince, Muley Abu-Abdallah, cast one long sad farewell look, “with a sigh,” over the glory forever lost, and retired to the lands assigned to him in the Alpujarras, but unable to overcome his dejection, he turned his steps to Africa. After nearly eight hundred years the whole Iberian Peninsula again became Christian, as it had been in the time of the Visigoths. But heaven could not rejoice over the conquest, which delivered fresh human sacrifices to the lords of hell. The Jews were the first to experience the tragic effect of the conquest of Granada.

After long and bloody strife the beautiful city of Granada fell into the hands of the proud Spaniards. Frivolous Muley Abu-Abdallah (Boabdil), the last king, signed a secret treaty with Ferdinand and Isabella (25th November, 1491) to give up the town and its territory by a certain time. The conditions, seeing that independence was lost, were tolerably favorable. The Moors were to keep their religious freedom, their civil laws, their right to leave the country, above all their manners and customs, and were only required to pay the taxes which hitherto they had paid the Moorish king. The renegades -- that is to say, Christians who had adopted Islam, or, more properly speaking, the Moorish pseudo-Christians -- who had fled from the Inquisition to Granada, and returned to Islam, were to remain unmolested. The Inquisition was not to claim jurisdiction over them. The Jews of the capital of Granada, of Albaicin quarter, the suburbs and the Alpujarras, were included in the provisions of the treaty. The were to enjoy the same indulgences and the same rights, except that relapsed Marranos were to leave the city, only the first month after its surrender being the term allowed for emigration; those who stayed longer were to be handed over to the Inquisition. One noteworthy point stipulated by the last Moorish king of Granada, was that no Jew should be set over the vanquished Moors as officer of justice, tax gatherer, or commissioner. On January 2nd, 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella, with their court, amid ringing of bells, and great pomp and circumstance, made their entry into Granada. The Mahometan kingdom of the Peninsula had vanished like a dream in an Arabian Night’s legend. The last prince, Muley Abu-Abdallah, cast one long sad farewell look, “with a sigh,” over the glory forever lost, and retired to the lands assigned to him in the Alpujarras, but unable to overcome his dejection, he turned his steps to Africa. After nearly eight hundred years the whole Iberian Peninsula again became Christian, as it had been in the time of the Visigoths. But heaven could not rejoice over the conquest, which delivered fresh human sacrifices to the lords of hell. The Jews were the first to experience the tragic effect of the conquest of Granada.

The war against the Mahometans of Granada, originally undertaken to punish attempts at encroachment and breach of faith, assumed the character of a crusade against unbelief, of a holy war for the exaltation of a cross and the spread of the Christian faith. Not only the bigoted queen and the unctuous king, but also many Spaniards were dragged by the conquest into raging fanaticism. Are the unbelieving Mahometans to be vanquished, and the still more unbelieving Jews to go free in the land? This question was too pertinent not to meet with an answer unfavorable to the Jews. The insistence of Torquemada and friends of his own way of thinking, that the Jews, who had long been a thorn in their flesh, should be expelled, at first met with indifference, soon began to receive more attention from the victors. Then came the consideration that owing to increased opulence, consequent on the booty acquired from the wealthy towns of conquered Granada, the Jews were no longer indispensable. Before the banner of the cross waved over Granada, Ferdinand and Isabella had contemplated the expulsion of the Jews. With this end in view, they had sent an embassy to Pope Innocent VII, stating that they were willing to banish the Jews from the country, if he, Christ’s representative, the avenger of his death, set them the example; but even this abandoned pope, who had seven illegitimate sons and as many daughters, and who, soon after his accession to the papal chair, had broken a solemn oath, was opposed to the expulsion of the Jews. Meshullman, of Rome, having heard of the pope’s refusal, with great joy announced to the Italian and Neapolitan communities that Innocent would not consent to expulsion. The Spanish sovereigns decided on the banishment of the Jews without pope’s consent.

From the enchanted palace of the Alhambra there was suddenly issued by the “Catholic Sovereigns” a proclamation that, within four months, the Spanish Jews were to leave every portion of Castile, Aragon, Sicily and Sardinia under pain of death (March 31, 1492). They were at liberty to take their goods and chattels with them, but neither gold, silver, money, nor forbidden articles of export-only such things as it was permitted to export. This heartless cruelty Ferdinand and Isabella thought to vindicate before their own subjects and before foreign countries. The proclamation did not accuse the Jews of extravagant usury, of unduly enriching themselves, of sucking the marrow from the bones of the people insulting the host, or crucifying Christian children -- not one syllable was said of these things. But it set forth that the falling away of the new Christians into “Jewish unbelief” was caused by their intercourse with Jews. The proclamation continued that long since it would have been proper to banish the Jews on account of their wily ways; but at first the sovereigns had tried clemency and mild means, banishing only the Jews of Andalusia, and punishing the most guilty, in the hope that these steps would suffice. As, however, this had not prevented the Jews from continuing to pervert the new-Christians from the Catholic faith, nothing remained but for their majesties to exile those who had lured back to heresy the people who had indeed fallen away, but had repented and returned to holy Mother Church. Therefore had their majesties, in council with the princes of the church, grandees, and learned men, resolved to banish the Jews from the kingdom. No Christian, on pain of confiscation of his possessions, should, after the expiration of a certain term, give succor or shelter to Jews. The edict of Ferdinand and Isabella is good testimony for the Jews of Spain in those days, since no accusations could be brought against them but that they had remained faithful to their religion, and had sought to maintain their Marrano brethren in it.

The long-dreaded blow had fallen. The Spanish Jews were to leave the country, round which thefibers of their hearts had grown, where lay the graves of their forefathers of at least fifteen hundred years, and towards whose greatness, wealth, and culture they had so largely contributed. The blow fell upon them like a thunderbolt. Abarbanel thought that he might be able to avert it by his influence. He presented himself before the king and queen, and offered enormous sums in the name of the Jews if the edict were removed. His Christian friends, eminent grandees, supported his efforts. Ferdinand, who took more interest in enriching his coffers than in the Catholic faith, was inclined to yield. Then the fanatical inquisitor, Torquemada, lifted up his voice. It is related that he took upon himself to rush into the presence of the king and queen, carrying the crucifix aloft, and uttering these winged words: “Judas Iscariot sold Christ for thirty pieces of silver; your highnesses are about to sell him for 300,000 ducats. Here He is, take Him, and sell Him!” Then he left the hall. These words, or the influence of the other ecclesiastics, had a strong effect upon Isabella. She resolved to abide by the edict, and, of bolder spirit than the king, contrived to keep alive his enmity against the Jews. Juan de Lucena, a member of the royal council of Aragon, as well as minister, was equally active in maintaining the edict. At the end of April heralds and trumpeters went through the whole country, proclaiming that the Jews were permitted to remain only till the end of July to set their affairs in order; whoever of them was found after that time on Spanish ground would suffer death.

Great as was the consternation of the Spanish Jews having to tear themselves from the beloved land of their birth and the ashes of their forefathers, and go forth to an uncertain future in strange lands, among people whose speech they did not understand, who, perhaps, might be more unfriendly towards them than the Spanish Christians, they had to bestir themselves and make preparation for their exodus. At every step they realized that a yet more cruel fate awaited them. Had they been able, like the English Jews at the end of the thirteenth century, and the French a century later, to take riches with them, they might have been able to provide some sort of miserable existence for themselves; but the Jewish capitalists were not permitted to take their money with them, they were compelled to accept bills of exchange for it. But Spain, on account of its dominant knightly and ecclesiastical element, had no places of exchange like those in Italy, where commercial notes were of value. Business on a large scale was in the hands, for the most part, of Jews and new-Christians, and the latter, from fear, had to keep away from their brethren in race. The Jews who owned land were forced to part with it at absurd prices, because no buyers applied, and they were obliged to beg the Christians for even the meanest thing in exchange. A contemporary, Andreas Bernaldez, pastor of Los Palacios, relates that the most magnificent houses and the most beautiful estates of the Jews were sold for a trifle. A house was bartered for an ass, and a vineyard for a piece of cloth and linen. Thus the riches of the Spanish Jews melted away, and could not help them with their day of need. In Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia, it was even worse with them. Torquemada, who on this occasion exceeded his former inhumanity, forbade the Christians to have any intercourse with them. In these provinces, Ferdinand sequestrated their possessions, so that not only the debts, but also the claims which monasteries pretended to have upon them were paid. This fiendish plan he devised for the benefit of the church. The Jews would thereby be driven to despair, and turn to the cross for succor. Torquemada, therefore, imposed on the Dominicans the task of preaching Christianity everywhere, and of calling upon the Jews to receive baptism, and thus remain in the land.

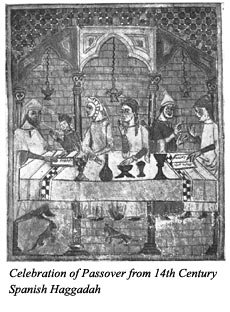

On the other side the rabbis bade the people to remain steadfast, accept their trials as test of their firmness, and trust in God, who had been with them in so many days of trouble. The fiery eloquence of the rabbis was not necessary. Each one encouraged his neighbor to remain true and steadfast to the Jewish faith. “Let us be strong,” they said to each other, “for our religion and for the Law of our fathers before our enemies and blasphemers. If they will let us live, we shall live; if they kill us, then we shall die. We will not desecrate the covenant of our God; our heart shall not fail us. We will go forth in the name of the Lord.” If they had submitted to the baptism, would they not have fallen into the power of the bloodstained Inquisition? The cross had lost its power of attraction even for lukewarm Jews, since they had seen upon what trivial pretexts members of their race were delivered over to the stake. One year before the proclamation of banishment was made, thirty-two new Christians in Seville were bound living to the stake, sixteen were burned in effigy, and 625 sentenced to penance. The Jews, moreover, were not ignorant of the false and deceitful ways in which Torquemada entrapped is victims. Many pseudo-Christians had fled from Seville, Cordova and Jaen, to Granada, where they had returned to the Jewish faith. After the conquest of the town, Torquemada proclaimed that if they came back to Mother Church, “whose arms are always open to embrace those who return to her with repentance and contrition,” they would be treated with mildness, and in private, without onlookers, would receive absolution. A few allowed themselves to be charmed by this sweet voice, betook themselves to Toledo, and were pardoned -- to a death of fire. Thus it came about that, in spite of the preaching of the Dominicans, and notwithstanding their indescribably terrible position, few Jews passed over to Christianity in the year of the expulsion from Spain. Among persons of note, only one rich tax-collector and chief rabbi, Abraham Senior, his son, and his son-in-law, Mer, a rabbi, went over, with the two sons of the latter. It is said that they received baptism in desperation, because the queen who did not want to lose her clever minister of finance, threatened heavier persecution of the departing Jews, if they did not submit. Great was the rejoicing at the court over the baptism of Senior and his family. Their Majesties themselves and the cardinal stood as sponsors. The newly baptized all took the family name of Coronel, and their descendants filled some of the highest offices in the state.

On the other side the rabbis bade the people to remain steadfast, accept their trials as test of their firmness, and trust in God, who had been with them in so many days of trouble. The fiery eloquence of the rabbis was not necessary. Each one encouraged his neighbor to remain true and steadfast to the Jewish faith. “Let us be strong,” they said to each other, “for our religion and for the Law of our fathers before our enemies and blasphemers. If they will let us live, we shall live; if they kill us, then we shall die. We will not desecrate the covenant of our God; our heart shall not fail us. We will go forth in the name of the Lord.” If they had submitted to the baptism, would they not have fallen into the power of the bloodstained Inquisition? The cross had lost its power of attraction even for lukewarm Jews, since they had seen upon what trivial pretexts members of their race were delivered over to the stake. One year before the proclamation of banishment was made, thirty-two new Christians in Seville were bound living to the stake, sixteen were burned in effigy, and 625 sentenced to penance. The Jews, moreover, were not ignorant of the false and deceitful ways in which Torquemada entrapped is victims. Many pseudo-Christians had fled from Seville, Cordova and Jaen, to Granada, where they had returned to the Jewish faith. After the conquest of the town, Torquemada proclaimed that if they came back to Mother Church, “whose arms are always open to embrace those who return to her with repentance and contrition,” they would be treated with mildness, and in private, without onlookers, would receive absolution. A few allowed themselves to be charmed by this sweet voice, betook themselves to Toledo, and were pardoned -- to a death of fire. Thus it came about that, in spite of the preaching of the Dominicans, and notwithstanding their indescribably terrible position, few Jews passed over to Christianity in the year of the expulsion from Spain. Among persons of note, only one rich tax-collector and chief rabbi, Abraham Senior, his son, and his son-in-law, Mer, a rabbi, went over, with the two sons of the latter. It is said that they received baptism in desperation, because the queen who did not want to lose her clever minister of finance, threatened heavier persecution of the departing Jews, if they did not submit. Great was the rejoicing at the court over the baptism of Senior and his family. Their Majesties themselves and the cardinal stood as sponsors. The newly baptized all took the family name of Coronel, and their descendants filled some of the highest offices in the state.

Their common misfortune and suffering developed among the Spanish Jews in those last days before their exile deep brotherly affection and exalted sentiments, which, could they have lasted, would surely have borne good fruit. The rich, although their wealth had dwindled, divided it fraternally with the poor, allowing them to want for nothing, so that they should not fall into the hands of the church, and also paid the charges of their exodus. The aged rabbi, Isaac Aboab, the friend of Abarbanel, went with thirty Jews of rank to Portugal, to negotiate with King Joao II, for the settlement of the Jews in that country, or for their safe passage through it. They succeeded in making tolerably favorable conditions. The pain of leaving their passionately loved country could not be overcome. The nearer the day of the departure came, the more were the hearts of unhappy people wrung. The graves of their forefathers were dearer to them than all besides, and from these they found parting hardest. The Jews of the town of Vitoria gave to the community the Jewish cemetery and its appertaining grounds in perpetuity, in condition that it should never be encroached upon, nor planted over, and a deed to this effect was drawn up. The Jews of Segovia assembled three days before their exodus around the graves of their forefathers, mingling their tears with the dust, and melting the hearts of the Catholics with their grief. They tore up many of the tombstones to bear them away as memorial relics, or gave them to the Moors.

At the last day arrived on which the Spanish Jews had to take staff in hand. They had been accorded two days in respite, that is, were allowed two days later than July 31st for setting forth. This date fell exactly upon the anniversary of the ninth of Av, which was fraught with memories of the splendor of the old days, and had so often found the children of Israel wrapped in grief and misery. About 300,000 left the land which they so deeply loved, but which now became a hateful memory to them. They wandered partly northwards, to the neighboring kingdom of Navarre, partly southwards, with the idea of settling in Africa, Italy or Turkey. The majority however made for Portugal. In order to stifle sad thoughts and avoid the melancholy impression which might have moved some to waver and embrace the cross in order to remain in the land, some rabbis caused pipers and drummers to go before, making lively music, so that for a while the wanderers should forget their gnawing grief. Spain lost in them the twentieth part of her most industrious, painstaking, intelligent inhabitants, its middle-class which created trade, and maintained its brisk circulation, like the blood of a living organism. For there were among the Spanish Jews not merely capitalists, merchants, farmers, physicians, men of learning, but also artisans, armors, metal workers of all kinds, at all events no idlers who slept away their time. With the discovery of America, the Jews might have lifted Spain to the rank of the wealthiest, the most prosperous and enduring of states, which by reason of its unity of government might certainly have competed with Italy. But Torquemada would not have it so; he preferred to train Spaniards for a bloodstained idolatry, where, pious men were condemned to chains, dungeons, or the galleys, if they dared even read the Bible. The departure of the Jews from Spain soon made itself felt in a very marked manner by the Christians. Talent, activity and prosperous civilization passed with them from the country. The smaller towns, which had derived some vitality from the Jews, were quickly depopulated, sank into insignificance, lost their spirit of freedom and independence, and became the tools for the increasing despotism of the Spanish king and the imbecile superstition of the priests. The Spanish nobility soon complained that their towns and villages had fallen into insignificance, had become deserted, and they declared that, could they have foreseen the consequences, they would have opposed the royal commands.

The Spanish Jews had such widespread repute, and their expulsion had made so much stir in Europe, that crowds of ships were ready in Spanish seaports to take up the wanderers and convey them to all parts, not only the ships of the country, but also Italian vessels from Genoa and Venice. The ship-owners saw a prospect of lucrative business. Many Jews from Aragon, Catalonia and Valencia desired to settle in Naples, and sent ambassadors to the king, Ferdinand I, to ask him to receive them. This prince was not merely free from prejudice against the Jews, but was kindly inclined towards them, out of compassion for their misfortunes, and he may have promised himself industrial and intellectual advantage from this immigration of the Spanish Jews. Whether it was calculation or generosity, it is enough that he bade them welcome, and made his realm free to them. Many thousands of them landed in the Bay of Naples (24th August, 1492), and were kindly received. The native Jewish community treated them with true brotherly generosity, defrayed the passage of their poor not able to pay, and provided of their immediate necessities.

Isaac Abarbanel, also, and his whole household, went to Naples. Here he lived at first as a private individual, and continued the work of writing a commentary upon the book of Kings, which had been interrupted by his state duties. When the king of Naples was informed of his presence in the city, he invited him to an interview, and entrusted him with a post in all likelihood in the financial department. Probably he hoped to make use of Abarbanel’s experience in the war with which he was threatened by the king of France. Whether from his own noble impulses, or from esteem for Abarbanel, the king of Naples showed the Jews a gentle humanity which startlingly contrasted with the cruelty of the Spanish king. The unhappy people had to struggle with many woes; when they thought themselves free of one, another yet more merciless fell upon them. A devastating pestilence, arising out of the sad condition to which they had been reduced, or from the overcrowding of the ships, followed in the track of the wanderers. They brought death with them. Scarcely six months had they been settled on Neapolitan soil when the pestilence carried numbers of them off, and King Ferdinand, who dreaded a rising of populace against the Jews, hinted to them that they must bury their corpses by night and in silence. When the pest could no longer be concealed, and every day increased in virulence, people and courtiers alike entreated him to drive them forth. But Ferdinand would not assent to his inhuman proceeding; he is said to have threatened to abdicate if the Jews were ill treated. He had hospitals erected for them outside the town, sent physicians to their aid, gave them means of support. For a whole year he strove with unexampled nobility, to succor the unfortunate people, whom banishment and disease had transformed into living corpses. Those, also, who were fortunate enough to reach Pisa found a brotherly reception. The sons of Yechiel of Pisa fairly took up their abode on the quay, so as to be ready to receive wanderers, provide for their wants, shelter them, or help them on their way to some other place. After Ferdinand’s death, his son Alfonso II, who little resembled him, retained the Jewish statesman, Abarbanel, in his service, and, after his resignation in favor of his son, took him with him to Sicily. Abarbanel to the last remained faithful to the prince in his misfortunes (January 1494, to June 1495).

After the conquest of Naples by the weak-headed knight-errant king of France, Charles VIII, the members of the Abarbanel family were torn apart and scattered. None of them, however, met with such signal misfortune as the eldest son, Judah Leon Medigo (born 1470, died 1530). He had been so well beloved at he Spanish court that they were loath to part with him, and would gladly have kept him there --of course, as a Christian. To attain this end, a command was issued that he be not permitted to leave Toledo, or that his one-year-old son be taken from him, baptized immediately, and that in this manner the father be chained to Spain. Judah Abarbanel, however, got wind of this plot against his liberty, sent his son, with his nurse, “like stolen goods,” secretly to the Portuguese coast; but as himself did not care to seek shelter in the country where his father had been threatened with death, he turned his face towards Naples. His suspicions of the king of Portugal were only too speedily justified. No sooner did Joao hear that a relative of Abarbanel was within his borders than he ordered the child to be kept as hostage, and not to be permitted to go forth with other Jews. Little Isaac never saw his parents and his grandparents again. He was baptized, and brought up as a Christian. The agony of the father at the living death of his lost child was boundless. It gave him no rest or peace to his latest hour, and it found vent in a lamentation sad in the extreme. Yet what was the grief for one child, compared with the woes which overtook the thousands of Jews hunted out of Spain?

The description by their contemporaries of the sufferings of the Jews make one’s hair stand on end. They were dogged wherever they went. Those whom plague and starvation had spared, fell into the hands of brutalized men. The report got about that the Spanish Jews had swallowed the gold and silver which they had been forbidden to carry away, intending to use it later on. Cannibals therefore, ripped open their bodies to seek for a coin in their entrails. The Genoese ship-folk behaved most inhumanly to the wanderers who had trusted their lives to them. From avarice, or sheer delight in the death agonies of the Jews, they flung many of them into the sea. One captain offered insult to the beautiful daughter of a Jewish wanderer. Her name was Paloma (Dova), and to escape shame, the mother threw her and her other daughters and then herself in the waves. The wretched father composed a heartbreaking lamentation for his lost dear ones.

Those who reached the port of Genoa had to contend with new miseries. In this thriving town there was a law that Jews might not remain there for longer than three days. As the ships which were to convey the Jews thence required repairing, the authorities conceded the permission for them to remain, not in the town, but upon the Mole, until the vessels were ready from sea. Like ghosts, pale, shrunken, hollow-eyed, gaunt, they went on shore, and if they had not moved, impelled by instinct to get out of their floating prison, they might have been taken for so many corpses. The starving children went into the churches, and allowed themselves to be baptized for a morsel of bread; and Christians were merciless enough not merely to accept such sacrifices, but with the cross in one hand, and bread in the other, to go among the Jews and tempt them to become converted. The longer they remained, the more their number diminished, through the passing over to Christianity of the younger members, and many fell victims to plagues of all kinds. Other Italian towns would not allow them to land even for a short time, partly because the Jews brought the plague with them.

The survivors from Genoa who reached Rome underwent still more bitter experiences; their own people leagued against them, refusing to allow them to enter, from fear that influx of new settlers would damage their trade. They got together 1,000 ducats, to present to the notorious monster, Pope Alexander VI, as a bribe to refuse to allow the Jews to enter. This prince, himself unfeeling enough, was so enraged at the heartlessness of these men against their own people, that he ordered every Roman Jew out of the city. It cost the Roman congregation 2,000 ducats to obtain the revocation of this edict, and they had to take they refugees besides.

The Greek islands of Corfu, Candia and others became filled with Spanish Jews; some had dragged themselves thither, others had been sold as slaves there. The majority of the Jewish communities had great compassion for them, and strove to care for them, or at all events to ransom them. They made great efforts to collect funds, and sold the ornaments of the synagogues, so that their brethren might not starve, or be subjected to slavery. Persians, who happened to be on the island of Corfu, bought Spanish refugees, in order to obtain from Jews of their own country a high ransom of them. Elkanah Kapsali, a representative of the Candian community, was indefatigable in his endeavors to collect money for the Spanish Jews. The most fortunate were those who reached the shores of Turkey; for the Turkish Sultan, Bajazet II, showed himself to be not only a most humane monarch, but also the wisest and most far seeing. He understood better than the Christian princes what hidden riches the impoverished Spanish Jews brought with them, not in their bowels, but in their brains, and he wanted to turn these to use for the good of his country. Bajazet caused a command to go forth through the European provinces of his dominions that the harassed and hunted Jews should not be rejected, but should be received in the kindest and most friendly manner. He threatened with death anyone who should illtreat or oppress them. The chief rabbi, Moses Kapslai, was untiringly active in protecting the unfortunate Jewish Spaniards who had come as beggars or slaves to Turkey. He traveled about, and levied a tax from the rich native Jews “for the liberation of the Spanish captives.” He did not need to use much pressure; for the Turkish Jews willingly contributed to the assistance of the victims of Christian fanaticism. Thus thousands of Spanish Jews settled in Turkey, and before a generation had passed, they had taken the lead among the Turkish Jews, and made Turkey a kind of Eastern Spain.

At first the Spanish Jews who went to Portugal seemed to have some chance of a happy lot. The venerable rabbi, Isaac Aboab, who had gone with a deputation of thirty to seek permission from King Joao either to settle in or pass through Portugal, succeeded in obtaining tolerably fair terms. Many of the wanderers chose to remain in the neighboring kingdom for a while, because they flattered themselves with the hope that their indispensableness would make itself evident after their departure, that the eyes of the now blinded king and queen of Spain would be opened, and they would then receive the banished people with open arms. At the worst, so thought the refugees, they would have time in Portugal to look round, decide which way to go, readily find ships to convey them in safety to Africa or to Italy. When the Spanish deputies placed the proposition before King Joao II to receive the Jews permanently or temporarily in Portugal, the king consulted his grandees at Cintra. In presenting the matter, he permitted it to be seen that himself was desirous of admitting the exiles for a pecuniary consideration. Some of the advisers, either from pity for the unhappy Jews, or from respect for the king, were in favor of granting permission; others and these the majority, either out of hatred for the Jews, or a feeling of honor, were against it. The king, however, overruled all objections, because he hoped to carry on the contemplated war with Africa by means of the money acquired from the immigrants. It was at first said that the Spanish refugees were to be permitted to settle permanently in Portugal. This favor, however, the Portuguese Jews themselves looked upon with suspicion, because the little state would thus hold a disproportionate number of Jews, and the wanderers, most of them penniless, would fall a heavy burden upon them.

The ancient family of Abarbanel did not escape heavy disasters and constant migrations. The father, Isaac Abarbanel, who had occupied a high position at the court of the accomplished king, Ferdinand I, and his son Alfonso, at Naples, was forced, on the approach of the French, to leave the city, and, with his royal patron, to seek refuge in Sicily. The French hordes plundered his house of all his valuables, and destroyed a choice library, his greatest treasure. On the death of King Alfonso, Isaac Abarbanel, for safety, went to the island of Corfu. He remained there until the French had evacuated the Neapolitan territory; then he settled at Monopoli (Apuli), where he completed or revised many of his writings. The wealth acquired in the service of the Portuguese and the Spanish courts had vanished, his wife and children were separated from him and scattered, and he passed his days in sad musings, out of which only his study of the Scriptures and the annals of the Jewish people could lift him. His eldest son, Judas Leon Medigo Abarbanel, resided at Genoa, where, in spite of his unsettled existence and consuming grief for the loss of his young son, who had been taken from him, and was being brought up in Portugal as a Christian. For Leon Abarbanel was much more highly accomplished, richer in thought, in every way more gifted then his father, and deserves consideration not merely for his father’s, but for his sake. Leon Abarbanel practiced medicine to gain a livelihood (whence his cognomen Medigo); but his favorite pursuits were astronomy, mathematics and metaphysics. Shortly before the death of the gifted and eccentric Pico de Mirandola, Leon Medigo became acquainted with him, won his friendship, and at his instigation undertook the writing of philosophical work.

Leon Medigo, in a remarkable manner, entered into close connection with acquaintances of his youth, with Spanish grandees, and even with King Ferdinand, who had driven his family and so many hundred thousands into banishment and death. For he became the private physician of the general, Gonsalvo de Cordova, the conqueror and viceroy of Naples. The heroic, amiable, and lavish De Cordova did not share his master’s hatred against the Jews. In one of his descendants Jewish literature found a devotee. When king Ferdinand, after the conquest of Naples (1504), commanded that the Jews be banished thence, as from Spain, the general thwarted the execution of the order, observing that, on the whole, there were but few Jews on Neapolitan territory, since most of the immigrants had either left it, or had become converts to the Christianity. The banishment of these few could only be injurious, since they would settle at Venice, which would benefit by their industry and riches. Consequently the Jews were allowed to remain a while longer on the Neapolitan territory. Leon Medigo was for over two years De Cordova’s physician (1505-1507), and King Ferdinand saw him when he visited Naples. After the king’s departure and the ungracious dismissal of the viceroy (June, 1507), Leon Abarbanel, having nowhere found suitable employment, returned to his father, then living at Venice, whither he had been invited by his second son, Isaac II, who practiced medicine first at Reggio (Calabria), then at Venice. The youngest son, Samuel, afterwards a generous protector of his co-religionists, was the most fortunate of the family. He dwelt amidst the cool shades of the academy of Salonica, to which his father had sent him to finish his education in Jewish learning.

The elder Abarbanel once more entered the political arena. At Venice he had the opportunity of settling a dispute between the court of Lisbon and the Venetian Republic concerning the East-Indian colonies established by the Portuguese, especially concerning trade in spices. Some influential senators discerned Isaac Abarbanel’s correct political and financial judgement, and thenceforth consulted him in all important questions of state policy. But suffering and travel had broken his strength; before he reached seventy years, he felt the infirmities of old age creeping over him. In a letter of reply to Saul Cohen Ashkenasi, an inhabitant of Candia, a man thirsting for knowledge, the disciple and intellectual heir of Elias del Medigo, Abarbanel complains of increasing debility and senility. Had he been silent, his literary productions of that time would have betrayed his infirmity. The baited victims of Spanish fanaticism would have needed bodies of steel and the resisting strength of stone not to succumb to the sufferings with which they were overwhelmed.

The very enormity of the misery they endured raised the dignity of the Sephardic Jews to a height bordering on pride. That they whom God’s hand had smitten so heavily, so persistently, and who had undergone such unspeakable sorrow, must occupy a peculiar position, and belong to the specially elect, was the thought or the feeling existing more or less in the breasts of the survivors. They looked upon their banishment from Spain as a third exile, and upon themselves as favorites of God, whom, because of His greater love for them, He had chastised the more severely. Contrary to expectation, a certain exaltation took possession of them, which did not, indeed, cause them to forget, but transfigured, their sufferings. As soon as they felt even slightly relieved from the burden of their boundless calamity, and were able to breathe, they rose with elastic force, and carried their hands high like princes. They had lost everything except their Spanish pride, their distinguished manner. However humbled they might be, their pride did not forsake them; they asserted it wherever their wandering feet fond a resting place.